By John Paul Lichon

Founder, Verso Ministries

This reflection recaps our recent pilgrimage, Holy Spirits on the Bourbon Trail, a young adult pilgrimage with the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend.

One of the oddities of pilgrimage is that, by journeying forward on one’s way, the missteps of the past both emerge with mysterious clarity, but in an equally mysterious way, disappear through the realization of God’s patience and mercy. Only in journeying forward do we understand how God’s Spirit has infused our steps all along…

In April 1808, the only diocese in the young United States, the Diocese of Baltimore, was divided to include four new dioceses: New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and you guessed it – Bardstown, Kentucky. The Diocese of Bardstown was to include the area of ten modern states – including Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, Tennessee, Michigan, Illinois, and more. It was the first inland diocese west of the Allegheny Mountains.

Benedict Joseph Flaget, a French missionary who had served in Indiana, Baltimore, and Cuba for over 15 years, was tapped to be the first bishop. Having already survived bouts of both smallpox (1793) and yellow fever (1798), Flaget promptly sailed to France to resist his appointment. He probably just wanted a desk job.

His plea fell on deaf ears, and so he traveled back to the States with five supporting missionaries to fulfill his obedience. Flaget spent the next four decades serving as Bishop of Bardstown (1808-1839), and then, when the Diocese moved to Louisville, as the first Bishop of Louisville (1839-1850). There was a brief stint in 1832 when he officially resigned due to poor health, only to be re-elected the following year after an outcry from the local clergy and faithful. Poor guy.

The history of the American Catholic Church is an often overlooked and underappreciated part of our identity. But it is precisely the humble (and obedient!) spirit of missionaries like Bishop Flaget that has paved the way for Catholicism in America to flourish. Sometimes we take for granted those upon whose shoulders we stand.

Case in point; if I’m being honest I will admit that the Holy Spirits Pilgrimage on the Bourbon Trail was not really planned with much of this in mind. The main draws were the Abbey of Gethsemani (the Trappist monastery known for its most famous resident – Thomas Merton) and the distilleries. We would spend time in prayer at pilgrimage sites like the Abbey and the Cathedral of the Assumption in Louisville, and in between, we’d have some fun at a few stops along the Bourbon Trail, tasting worldwide brands like Maker’s Mark. It was to be a pilgrimage that spanned the oppositions of sacred and profane, secular and religious, community and solitude, contemplation and action – as a way to discover God’s spirit moving through it all. It was a time to “renew your spirit,” as it were – not a deep dive into U.S. Catholic history.

But in reflecting on our pilgrimage, I am continually struck by the service and humility of a man like Flaget – a man who actively resisted where God was inviting him to serve, yet also a man whose courage pioneered the expansion of the Church into the wild west.

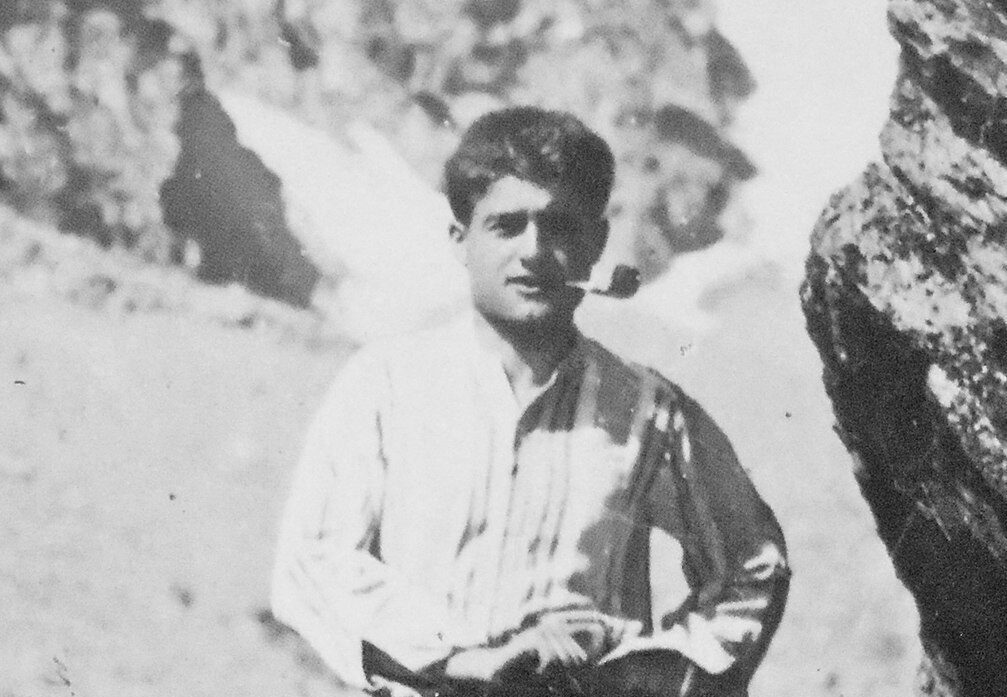

A similar, but different tension seems to be found within a man like Thomas Merton – the monk who was center stage in our visit to the Abbey of Gethsemani. Merton entered a cloistered monastery in rural Kentucky only to become a world-famous spiritual writer with a book on the New York Times bestsellers list for almost an entire year (his autobiography: The Seven Storey Mountain, in case you were wondering). Despite between a contemplative who cherished silence and solitude, he also conversed with many world leaders and revolutionaries of his day. He was constantly seeking dialogue and conversation to fuel his search for truth.

The cloister walls actually helped to ground Merton. They provided the structure and the stability to be able to accomplish his writing, to focus and hone his talents, and to actually give him the freedom to fulfill his vocation as an author (and monk and social justice advocate). But there always seemed to be this restlessness within him – this desire to travel far and wide, to converse with the world’s luminaries, to engage the secular milieu from which he had chosen to separate.

On Saturday morning, we spent a considerable amount of time with Brother Gregory – one of the monks who has been at the monastery for ten years. Brother Gregory shared with us many stories about his life in the monastery, about Merton, and about the vows that all Trappist monks and nuns take. These vows include vows of obedience, stability, and conversion of life. He spoke about the “martyrdom of the ego” which monks (and all Christians, if you think about it) must face in order to most fully serve God and others in humility, love, and grace. It strikes me that both Flaget (although not a Trappist) and Merton (maybe not the most exemplary contemplative monk) truly embraced that notion – to selflessly give of their lives in the service of God – despite their personal plans and preferences.

God’s Spirit works in remarkable ways. This pilgrimage continually reminded me that the Holy Spirit operates in and through us despite our limitations: despite our attempts to actively resist God’s call, despite the restlessness of which we are never completely purified, and despite my planning a pilgrimage in which the historical foundations were basically an afterthought. Yet Bishop Flaget, Thomas Merton, and even a lowly minister like myself discovered God’s gracious guidance and patient correctives along the way. I do not doubt that even the work of charring barrels and distilling bourbon are somehow included in the Holy Spirit’s plans. And for all of that, I say we raise a glass in thanksgiving.

John Paul Lichon is the Founder of Verso Ministries and certainly enjoys a nice bourbon at the end of a long day’s work. Or at any time of day, really.